“Russian women, especially on the first date, expect you to rape them.”

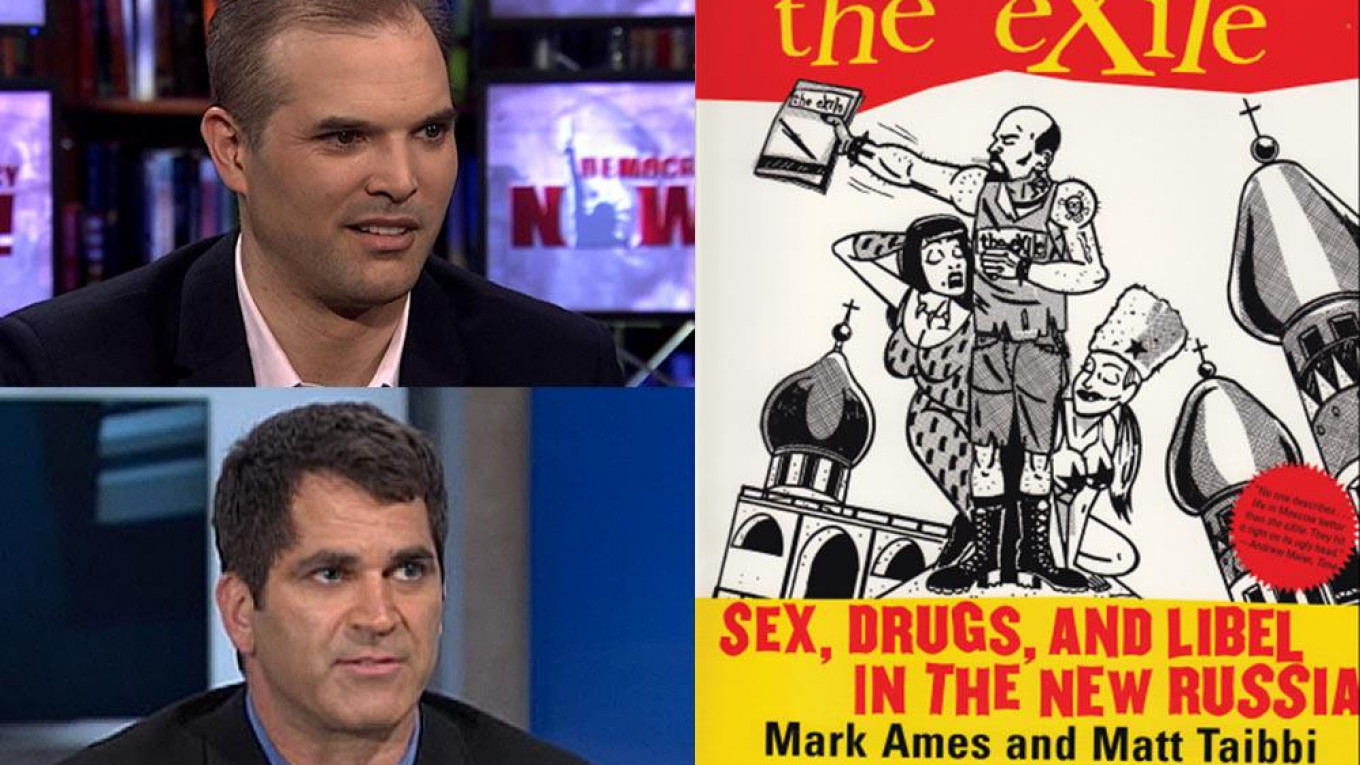

Journalist Mark Ames said this to an interviewer all the way back in 2000, when he and his then-colleague Matt Taibbi were busy promoting a book called “The eXile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia.”

The book, which was marketed as nonfiction, was rife with comments far worse than that example. Their account of life in Russia gleefully detailed sexual assault and abuse, both inside the office of The eXile — an expat-oriented publication in Moscow founded in 1997 and shuttered 11 years later — and outside it.

Today, both Ames and Taibbi say that when they were writing and speaking about violence against women, it was all satire. Specifically, they say, it was satire directed at misogynist expat men.

“Without trying to sound pompous — but there's no other way — satire was the approach to writing and publishing. And our interviews or public performances [was] where we'd ham it up, like loathsome expat idiots,” Ames told me over e-mail the other day.

For anyone who has written about Russia and talked to other writers on the beat, the nihilism of Ames and Taibbi’s old writing is nothing new. Some say it merely captured the zeitgeist in a lawless country. For others, it was loathsome garbage.

The fact that the Harvey Weinstein scandal has reignited the debate around this writing is seen by their admirers as tedious. Others view the damage to Ames and Taibbi’s reputations as just reckoning.

But few of us have stopped to consider the effect this kind of writing has had on how Russian women are seen.

I came to work in Moscow in 2010, two years after The eXile shuttered. But the idea that Ames and Taibbi were brave revolutionaries who paved a path for Western men to “enjoy” Russian women was everywhere.

The internet, likewise, brimmed with praise for the stereotype they helped craft – just check out some of the gushing reviews of their book, delighting at Ames’ exploits with “whores,” praising the authors as “people who get off on telling the truth,” and romanticizing their work as a just rebellion against Western “sexlessness.”

Don’t want to be staid and sexless? Come to Russia, where sexual assault is not only allowed, but expected — if you’re a man, that is. If you’re an expat woman, keep your boring, unattractive ass at home — you’re no match for gorgeous whores who beg to be abused.

That’s the gist of Ames and Taibbi’s writing about Russian women. To suggest that it hasn’t fed misogynist caricatures of the country is to be woefully naïve.

A caricature is easily dismissed as inconsequential — unless you feel its effects directly.

Never quite a “real expat” and never “an actual Russian” either, I’ve had to deal with everything from men kindly explaining to me that my Western upbringing has “corrupted” me, to aggressive, demeaning behavior that was followed up with, “for someone with a Russian name you sure are uptight” when I pushed back against it.

The stereotype of the Russian woman as perpetually sexually available is harmful precisely because it has consequences.

“[Ames and Taibbi] never struck me as violent,” a Moscow friend who said she partied with The eXile crew in the 1990s and wished to remain anonymous for the sake of her family’s privacy told me the other day.

“But do I know without a doubt that [their work] helped legitimize disrespectful behavior? Yes. Men wanted to believe those stories [of sexual assault] were real.”

A caricature is easily dismissed as inconsequential, unless you feel its effects directly

Since then, Taibbi has publicly apologized for using cruel and misogynistic language.

After I quoted misogynist praise of his work on Amazon to Ames, he said “I don't read Amazon reviews of my books. ‘Hell is other people reviewing on Amazon’ as John Dolan once wrote. And whatever you quoted there just reinforces how right he was.”

No one has come forward to accuse Ames and Taibbi of sexual assault. Zalina Abdulsalamova, who worked at The eXile for the last two years of its operation — after Taibbi had already left — described a professional and respectful environment to me.

“We hung out a lot together,” Abdulsalamova said of Ames and her other colleagues. “There was never any violent or demeaning behavior. It’s shocking to me that [Ames] could even be accused of that.”

As for their book publishers, a representative of Grove Atlantic (formerly Grove Press), told me that, “This book combines invented satire and nonfiction reporting and was categorized as nonfiction because there is no category for a book that is both.”

On the other hand, Ames and Taibbi continue to serve as examples of “brutally honest” writing about Russia – and I do have to wonder where the line between fact and fiction lies for their admirers.

I also wonder whether or not we can finally begin the conversation about how romanticizing Russia’s “wild” years, which, by the way, continue, can serve to dehumanize people who are most vulnerable to the “wilderness” they are living in.

Lots of people can boast about having a fun and interesting time in Moscow. Some can even do it without demeaning people.

But if you’re an expat whose definition of “brutal honesty” boils down to “a neocolonial fantasy of an exotic land where I can be as much of an assh-le as I want – then safely go home after I’m bored with it” – then maybe it’s time to admit that the real wilderness — dark, ugly, shabby and depressing — is in you.

And you will take it with you wherever you may go.

Natalia Antonova is an American writer and journalist.

The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.